Posted 22nd July 2019

This blog was written by Charlotte Österman, Partner and Sustainable Development Director of international development consultancy Pax Tecum Global, and Advisor to Social Value UK’s Council.

Through virtual and transportation advancements, our communities are getting closer and closer. Rural no longer means distant; with globalisation, we not only travel more than ever, we share a marketplace and economy. This is supported by development of infrastructure, logistics, education and governance; but also lifestyles and values that are becoming increasingly mainstreamed. It can be somewhat mind-blowing to consider that today, there is a farmer in rural sub-Saharan Africa using the same mobile phone to check the weather, as you are in reading this article.

But not everyone is convinced that the direction of development is all positive. For example, there’s the New Economics Foundation that sets out to change the current doctrine and economy, to one that works for the people and planet. Other economists have gathered in the Promoting Economic Pluralism movement, as a response to a perceived too one-sided way of viewing and analysing the economy. There are also counter-development movements, such as Local Futures, saying that a shift of direction is needed. Development has often been delivered in combination with an altruistic aspiration of “helping the poor”, as we’ve given with access to things we think they need. This includes health care, education, roads, heating, cooling, mobile phones; but we’d also gifting them with new values, plastic bottles, new sunglasses for every summer, t-shirts made by children, insulation, increased income differences and heaps of waste. “Of course”, development is positive to help develop a locality. Or is it really?

What the current development paradigm too often misses is the link to what is local. Did we ask before giving? And did we provide a fair picture of what development would look like? As with an example from Latin America – does the Mexican and Western-inspired telenovela with material richness and exciting dramas, that people in the poverty-stricken rural village of Nicaragua watch on a shared TV, provide a fair picture of what a developed society is?

This missed link to local and one-sided (positive) picture of development, is why village of Ladakh in the Indian Himalayas somewhat lost of their sense of identity, culture and sustainable system. When replacing values that are seemingly inappropriate in the developed world – such as a perfectly circular resource system and polygamic relationships that were not linked to (masculine) values or dominance, but systems where nothing or no one was left behind – with a semi-western system that does have schools and an financial economy, but also income differences, poverty, donations of school books in a language most locals don’t speak, as well as landfill.[1][

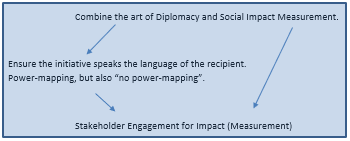

But this is where we can learn and do better, when linking the theories of diplomacy (which includes practices such as power mapping of influential stakeholders and political will identification) with a core idea of social impact measurement.

The concept of power mapping can be used to understand who are the important decision makers in the locality (community, city, country) that will need to be negotiated with in order to ensure the success of a proposed development initiatives (whether an NGO program or a new business entering new market). In addition, power mapping not only provides an outline of people in power, but also one of those who aren’t in power. This is key in order for us to link to a theme of social impact measurement, already at the start, which could help us better design for social impact valuable for all.Social Value International, originating from the former Social Return on Investment (SROI) network, offers the closest to a universally acknowledged approach to social impact measurement that there is. First and foremost, they state that any attempt to measure social impact should start with measuring the changes that the affected stakeholders experience and use the first principle of Social Value, Involve stakeholders, to determine this. Basically, this argue that you can’t claim any value or impact, unless you’ve consulted the people whose lives you are setting out to change.[2][

Nevertheless, all too often, this seems to be a principle missed. Not only at the measurement stage, when we count meals delivered, money invested/donated and internships provided instead of asking the stakeholders what changes they’ve experienced, but also at the offset of when we design an intervention.

We need to use the same principle as we do for measurement for intervention design and only then we can start developing development that is more holistically beneficiary. With this rational, we need to add in a pre-step to the principle above.

Step 1: Before involving your stakeholders for measurement, involve your stakeholders for design. And actually listen to them.

It is not always easy, when turning up with a great idea that you’d like to get the buy-in for, to start with listening. But this is a virtue that diplomacy can teach us. We need to think differently, because it is not that we are not doing our market research or needs assessments – in fact we are doing that! But more often than not, a tendency is to ask leading questions that we want answered to support for what we’re already proposing, instead of asking and actually listening to who the people that we often like to call beneficiaries.

What are the things they value highest in their locality? What are their strengths? What do they already do well and what can we learn from them? If we build this into our processes of development, we could start learning more from each other, instead of simply providing solutions from our part of the world that might have contextual negatives. Through transparent discussions around risks (incl. cultural) of the project and development, we’d be in a better place to co-design an intervention, as well as measuring the outcome. This would set grounds for more a collaborative and impact focused sustainable development – not only a one-way approach to “help develop” the poor.

By:

Charlotte Österman

Partner & Director of Sustainable Development

Pax Tecum Global Consultancy

[1] Helena Norberg-Hodge, Ancient Futures, 1991 (2016).

[2] Social Value International, The Seven Principles of Social Value, 2015. Available: https://sv-test.wp-support.team/resource/principles-of-social-value/